““We may think that the content of American movies is free from government interference, but in fact, the Pentagon has been telling filmmakers what to say — and what not to say — for decades. It’s Hollywood’s dirtiest little secret,” journalist Dave Robb wrote in his 2004 book, Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies.

It documented and exposed the extent to which Hollywood was complicit in the United States military’s “campaign to covertly manipulate” opinions around “world politics, American history, the nature of war, and above all, the image of the American military establishment itself.”

On December 8, according to Deadline, Robb died. He had recently been diagnosed with “inoperable cancer of the brain stem.”

In 2023, there are a number of journalists that cover the beat of military or government influence over film and television productions. But in the 2000s, Robb practically stood alone as one of the only reporters willing to take on the military industrial-complex.

Robb’s book detailed the influence of the Pentagon over numerous films, such as “Attack” (1956), “The Last Detail” (1973), “Stripes” (1981), “The Right Stuff” (1983), “Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home” (1986), “Top Gun” (1986), “No Way Out” (1987), “The Hunt For Red October” (1990), “Clear and Present Danger” (1994), “Forrest Gump” (1994), “Renaissance Man” (1994), “Crimson Tide” (1995), “Goldeneye” (1995), “The Tuskegee Airmen” (1995), and “Independence Day” (1996).

Pentagon influence over “Air Force One” (1997), “G.I. Jane” (1997), “Tomorrow Never Dies” (1997), “Armageddon” (1998), “Deep Impact” (1998), “The Perfect Storm” (2000), “Thirteen Days” (2000), “Behind Enemy Lines” (2001), “Black Hawk Down” (2001), “Jurassic Park III” (2001), “Pearl Harbor” (2001), “The Sum of All Fears” (2002), and “Windtalkers” (2002) was also outlined.

Remarkably, one of the officials Robb scrutinized was Phil Strub, who also died recently. Strub was the military’s chief propagandist in the Pentagon’s liaison office. He held the view that “any film that [portrayed] the military” negatively was “not realistic,” and therefore, “inaccurate.”

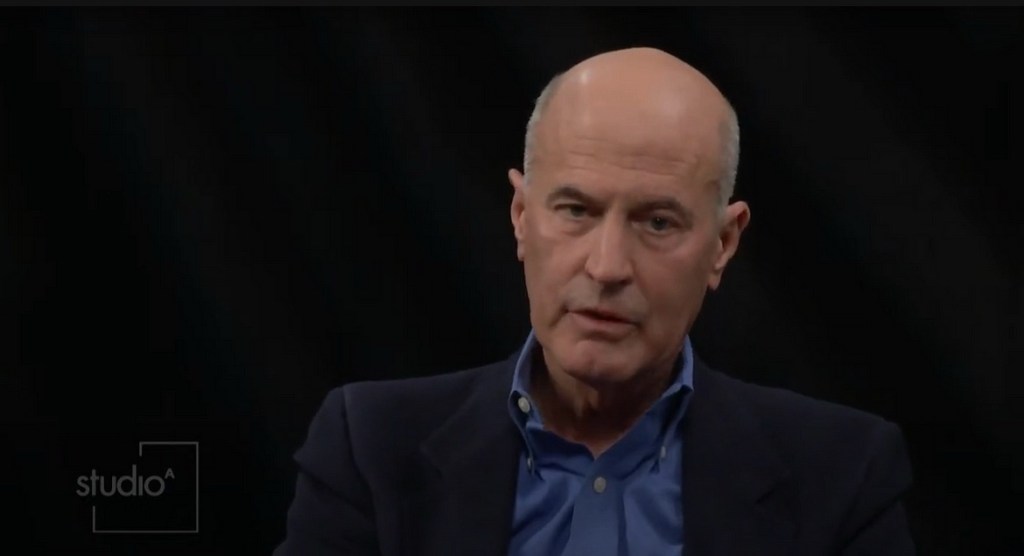

Journalist Tom Secker, co-author of National Security Cinema: The Shocking New Evidence of Government Control in Hollywood, broke the news of Strub’s death.

“A few days ago I was contacted by Phil’s brother, Terence, offering the news of his passing after a period of illness,” Secker wrote. “Terence was looking for someone to do a positive obituary, and evidently because this site ranks so highly on search engines for the term ‘Phil Strub,’ he emailed me. He offered up the info that Strub has been buried at Arlington National Cemetery, next to his father (a military doctor) and mother.”

Secker noted that soon after Terry emailed him with a request to honor a longtime propagandist with an obituary that lied about his life.

“Terry emailed to ask that I praise Phil Strub’s accomplishments and not make any ‘negative accusations,’” Secker shared. “I mulled this over and offered him a feature interview wherein he could say what he wanted to say about his brother, and I would publish it without editorializing or injecting my own opinions. He did not respond.”

Even more incredible, Secker asked the Pentagon’s public affairs office to confirm that Strub had died. They wildly claimed he was a “private citizen,” and they had “no current information.”

Let’s honor both Robb and Strub by highlighting some examples of censorship that Shrub himself imposed on movies that requested U.S. military equipment, vehicles, and other forms of support.

As Robb revealed, Strub had the filmmakers behind “Tomorrow Never Dies” remove a joke about the U.S. military losing the Vietnam War.

James Bond (Pierce Brosnan) was supposed to “parachute into the waters off Vietnam.” The “original draft” had “a rogue CIA agent, to be played by Joe Don Baker,” warning Bond not to be captured. “You know what will happen. It will be war, and maybe this time we’ll win,” the agent said.

That line was censored after it became clear that Strub would not give up pressuring producers.

For “Goldeneye,” Strub was offended that the first draft had an American admiral who was duped by a “seductive member of the Russian mafia to steal his identification badge.” If the production wanted access to Marines and Marine helicopters, they had to change the admiral’s nationality, which they did.

Strub pressured producers involved in “Clear and Present Danger” to make the President of the United States less hellbent on revenge after his friend was murdered. They also had the script changed so it no longer had a navy jet shooting down “an unarmed civilian airplane” that was “transporting a shipment of cocaine.”

On December 8, 1993, after the film’s production was complete, Major David Georgi boasted in a report that “military depictions [had] become more of a ‘commercial’ for us, more than damage control, and the production [offered] good public information value.”

Strub “hated the script” for “Thirteen Days,” which starred Kevin Costner and depicted the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. He believed the Joint Chiefs of Staff came off as “too hawkish and one-sided” and accused the filmmakers of creating “revisionist history.”

“Both General Curtis LeMay and General Maxwell Taylor (chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) are depicted in a negative and inauthentic way as unintelligent and bellicose,” Strub wrote in a letter on July 28, 1998, where the rejected the producers’ request for military assistance. (Note: LeMay was well-known for firebombing Japan and pushing for the use of nuclear weapons during the Cold War.)

In this instance, according to Robb, the production declined to comply with the Strub and the Pentagon. They turned to the Philippines for “broken down 1960s-era jet fighters, painted them up, and pulled them around on the ground with trucks to make it appear that they were taxiing on the runway.” A digital effect helped them simulate a U2 plane in flight.

Though it cost much more, the producers were able to make a movie that was not clear propaganda.

Strub was willing to assist producer Jerry Bruckheimer on “Armageddon,” especially because Bruckheimer has always been willing to let the U.S. military put a stamp on his projects. But “Crimson Tide” starring Denzel Washington and Gene Hackman was too much for Strub.

“We didn’t work on it because of the mutiny,” Strub told Robb. “We couldn’t get past the mutiny.”

Finally, Strub played a key role in ensuring that James Webb, a Vietnam War veteran (elected to the U.S. Senate in 2006), would not be able to get his book Fields of Fire adapted into a film with Pentagon support.

A letter to Webb that was written by Strub in 1993 complained about the script. “The Marines, under extreme pressure and frustration caused by the deadly and confusing nature of the war, react by committing egregious acts such as fragging (page 59), using illegal drugs (page 94 and elsewhere), executing suspected Viet Cong (page 94), and burning a villager’s ‘hootch’ (page 80).”

“Our concern is that these kinds of frequent, seemingly commonplace acts will obscure the act of bravery and dedication that the Marines displayed throughout the war in Vietnam.”

Strub added, “That these kinds of criminal activities actually took place is a matter of record. But by providing official support to the film, the Marines and the Department of Defense would be tacitly accepting them as everyday, yet regrettable, aspects of combat.”

Or put another way, accurately depicting crimes committed by soldiers during a war would give moviegoers the idea that such crimes were committed often. That just could not be allowed to undermine the myth-making objectives of Strub and the Pentagon liaison office.

Beyond Strub, thanks to Robb’s journalism it became more widely known that the Pentagon used “Lassie” and “The Mickey Mouse Club” to “target children as future recruits.” The Pentagon forced both shows to rewrite episodes “at the Pentagon’s insistence to make the armed forces more attractive to children.”

Robb veered into uncovering the relationship between the Pentagon and Hollywood, but he spent most of his career as a Hollywood labor reporter.

Mike Fleming Jr., the co-editor-in-chief for Deadline’s film section, penned a moving tribute to Robb, who he described as first and foremost committed to “rooting out wrongdoing”

“The subjects ranged from rooting out convicted pedophiles who resided in a home that was commonly used to house child actors in town on productions, to his final bylined piece about an NRA-funded government program that teaches children to shoot guns, even as bodies pile up each year from mass shootings often perpetrated by young people with emotional problems,” Fleming recalled.

“Prior to Deadline, Dave served five stints at The Hollywood Reporter — each interrupted by his resignation when the trade wouldn’t publish something provocative he uncovered. He served a stint at Variety, wrote investigative books, and wrote for the New York Times, Associated Press, LA Weekly, Los Angeles Daily News, Spy magazine and The Nation.”

Fleming also mentioned, “He was an advocate for the under-represented and disenfranchised in Hollywood: African-American and Native American actors, child actors, stunt performers, women. He exposed Hollywood’s dirty little secret, of not crediting screenwriters for their contributions on major movies because they’d been blacklisted in that shameful communist witch hunt. Robb helped writers living and dead get their due on films that included Lawrence of Arabia.”

Robb fortunately lived long enough to see the Writers Guild of America (WGA) and Screen Actors Guild and American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) effectively prevail in their strikes against greedy studio and company executives who refused to bargain with them on a fair contract.””

Credit & Publication: Kevin Gosztola’s Substack. Published: December 12th 2023. Source Link: https://gosztola.substack.com/p/the-tenacious-journalist-who-exposed?r=5ords&utm_medium=ios&utm_campaign=post